|

|

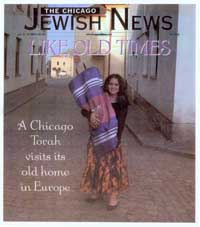

A Chicago Torah Visits its Old Home in Europe

This is the story of a citizen of a lost Jewish community in the Czech Republic who-with help from members of the U.S. Congress, no less-returned home for a visit and was received with wild enthusiasm by the residents of a town where no Jews survived. It's also the story of the bond that grew between members of a Chicago synagogue and the non-Jewish residents of a small European town, a town whose children even today mourn and honor their Jewish neighbors who perished in the Holocaust. Participants in this drama call it unique, incredibly powerful, life changing. But the star player can't say anything- not directly, anyway-because the citizen who returned for a brief visit home is a Torah. The story-the modern part of it anyway- really begins in 1967 when Rabbi Robert Marx, then the Reform movement's regional director for the Midwest, helped a congregation in Beloit, Wis. apply for a Holocaust Torah from London's Westminster Synagogue. Under a complex deal involving the Czech government, a prominent British art dealer and a London Jewish philanthropist, that synagogue in 1963 had become the repository for more than 1,500 Torah scrolls the Nazis had confiscated from synagogues in then- Czechoslovakia. The scrolls, many of them in poor condition, were repaired, then an organization, the Czech Memorial Scrolls Trust, was formed to find new homes for the ones that were able to travel. One of the Torahs found its way to Rabbi Marx, but by that time the congregation it was supposed to go to had folded. Marx kept it until 1984, when he founded Congregation Hakafa in Glencoe. There the Torah has reposed ever since, used only once a year, on Yom Kippur, for the reading of the Holiness Code, read in the afternoon just before the Yizkor service. (Many congregations that possess so-called Holocaust Torahs use them only on the most solemn occasions out of deference for the Jews who perished.) Things might have stayed that way had Rabbi Bruce Elder, now Hakafa's spiritual leader, not received a call two years ago from Dr. Stanton Canter, a California man who had traveled through the Czech Republic several years before. During those travels Canter came across a small town called Lostice in the Moravia region and was astounded to discover that, although there had been no Jews there since they were rounded up by the Nazis around 1939, the non- Jewish residents had maintained the town's Jewish cemetery and repaired an old synagogue. Why? "The non-Jewish community had such warm feelings toward the Jewish community because there had been harmonious relationships for 350 years," Elder relates. Canter joined with a local man, Ludek Shteipel, to form a foundation, Respect and Tolerance, designed to teach those very virtues, along with the history of the town, to local schoolchildren. He also continued researching the history of Lostice (pronounced Lo-STEECH-a) and was able to trace Hakafa's Torah back to it. At almost the same time the citizens of Lostice had been putting the finishing touches on the rebuilt synagogue and were beginning research to find out where "their" Torah ended up. It was just one of many coincidences connected with the trip. Canter called Rabbi Elder to ask if, for the town's 450th anniversary celebration, he could take a picture of the Torah and send it to the mayor. Elder did so, and the picture, along with a letter the rabbi sent, now hangs in a place of honor on the wall of the old synagogue, where the anniversary celebration was held. The mayor, Dr. Ctirad Lolek, was thrilled-and sent Elder and his congregants an invitation to visit Lostice. Two years later, they accepted. Elder, himself the son of a Holocaust survivor from Hungary, decided after corroborating the information that the Torah's provenance was authentic that "it would be a real powerful thing to take our Torah back"-but only for a visit, as it was not needed in a town where there are no longer any Jews. The decision to bring the Torah back to its home was occasioned by "all the voices that cry out from it that don't have the opportunity to come back. We had the opportunity to bring them back to their synagogue," he says. In addition, it would be a way to thank the non-Jews of Lostice for maintaining the memories and memorials of their Jewish neighbors. The occasion would mark the first worship service held in the Lostice synagogue in more than 60 years and, as it turned out, the first time a Czech Torah has returned to its homeland. The rabbi, along with 16 congregants, began making plans for the trip. But there was a problem. How to transport the Torah, which is nearly five feet tall and weighs 125 pounds? There was no seat available for the scroll on the plane the congregants were taking, and besides, "it wasn't feasible to be shlepping it on a plane," Elder says. "It's in very good shape but it is 200 years old and is fragile. It had to go through Customs, and we needed a way to get it over there safely." He wondered whether it could be shipped through a "diplomatic pouch," a form of transport the U.S. government uses to send items to its embassies, and contacted U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky's office to find out. Schakowsky, who is Jewish and whose district includes Chicago's northern suburbs, "took (the problem) and ran with it," Elder says, calling her "an amazing, unbelievable person. Without asking, she took all these steps to find a way to get the Torah there safely," he says. For her part, Schakowsky says, "I was thrilled to be asked to be involved. Nothing like this had ever been done successfully with the Czech Republic." She first contacted the U.S. ambassador in Prague, who recommended against using a diplomatic pouch. Schakowsky then assigned a legislative assistant, Robert Marcus, to the problem and together they contacted Rep. Tom Lantos, himself a Holocaust survivor and the ranking Democrat on the International Relations Committee. Marcus is a Wilmette native whose family members belong to Congregation Hakafa. Lantos recommended using the shipping company DHL, which is owned by a friend of his and, he noted, has expertise in shipping valuable objects. The firm "not only offered their help but really went out of their way," Schakowsky says, flying the Torah for free on a chartered flight, then coordinating its arrival with the U.S. State Department and the U.S. embassy in Prague. "Everyone who heard the story was touched and moved and looked for ways to be helpful, to be part of this very exciting, moving historic event," Schakowsky says. Elder noticed that reaction too. "The coordinating that went on to get the Torah there and back was amazing," he says. So was "the outpouring of support, people rallying around this object. It's just an object but it represents so much more so many people." Finally the Torah arrived and on Friday, June 17, so did the 16-member delegation from Hakafa, plus Marcus, Schakowsky's legislative aide, who became so caught up in the drama that he arranged his vacation so that he could go along. Even after the exchange of letters with the town's mayor, Elder says, the congregants were unprepared for what awaited them in Lostice. Some 150 people-mostly non-Jews from the town, but a few Jews from surrounding areas- turned out to greet them at the town hall, where the mayor and community leaders waited. In addition a handful of Jews from Prague, 80 miles away, had heard about the event and traveled to Lostice to be a part of it. The crowd traveled with the Hakafa delegation through the streets of the city to the synagogue, where the Torah was placed in the Ark for the first time since the late 1930s. A number of reporters were present as well, and the visit was well covered in the Czech press, with stories appearing in every major newspaper under headlines like "The synagogue revived by worship" and "The 19th-century Lostice Torah is back." In the synagogue, meanwhile, the Chicagoans found a number of benches as well as parts of stained glass windows from a synagogue at the nearby town of Olomouc that was completely destroyed by the Nazis. After the war, survivors found some of the benches; rescued them and installed them in a local church as a Holocaust memorial. Then, with financial help from Jews all over the world, including Congregation Hakafa, the respect and Tolerance Foundation acquired the benches and installed them -- 21 seats in all-in the Lostice synagogue. Each seat is dedicated to an individual, including the rabbi of the Olomouc synagogue, who perished at Treblinka; Rabbi Elder; and Elie Wiesel, who is an honorary member of the foundation. The Lostice synagogue had fared better than its neighbor, but not by much. It, too, had been partially destroyed by Nazi troops, with some walls knocked down and other parts burned. After the war, the citizens of the town decided to rebuild it as a tribute to the Jewish neighbors they had lost. They found the ancient blueprints in the town hall and used them to reconstruct the synagogue. The blueprints now hang on its wall in a frame. Marcus found that bit of enterprise amazing. "This was not a wealthy town," he says, "and they did this anyway even though there were no Jews there." In this setting, the ceremonies began with a Shabbat service during which the Torah was, for the first time since it originally left Lostice, unscrolled to the portion of the week, which Elder and other congregants read to a packed audience. The Lostice mayor and other community leaders participated as well, along with a representative of the Prague Jewish community and one from the U.S. embassy. A children's choir from the town had learned Jewish songs for the occasion and sang them at the service. "To hear 'Sholom Aleichem' in beautiful three-part harmony in a synagogue that hadn't had Jewish voices in it for years-it was impossible not to be transformed by it," Elder says. "The walls were crying, we were all crying. The Torah represents so much-the human will to rise above hatred. We all came away very different people. It touched each of us individually, so deeply, so profoundly." One of those who was affected was Hakafa congregant Judith Joseph, who was marking exactly 36 years (or as she says, "double chai") since her own bat mitzvah-so the parsha was the same one as hers. Only then she, like other girls and women, had not been allowed to read from the Torah. Instead, she did so at Lostice. "For the first time in my life I got to chant my Torah portion," Joseph says. "It was so thrilling to chant Torah in that building where it hadn't been chanted in 60 years. I felt like it was such a privilege." For Jerry Friedman, one of the founding members of Hakafa and its first president, the highlight of the trip was "the first moment, bringing the Torah and placing it in the Ark, then being able to hold a service there in a room packed with people from the town. That was very moving." After the service the congregants spread the Torah out on a table and mingled with the guests at a reception, which also included an exhibit of Jewish art that the Respect and Tolerance Foundation had hung on the synagogue walls. "For an hour and a half, people walked past the Torah, looking at it and taking pictures of it," Friedman reports. "They didn't want to leave." Marcus says he will never forget "the look in the people's eyes when we brought the Torah in. They knew this is a treasure. The rabbi asked the mayor if he would like to hold it and he was so honored and so scared-he didn't want to drop it." He, too, was impressed with the "hundreds of people who lined up to look at the Torah. The look on their faces-this was part of their town, their history. It was very touching." Despite the language barrier "there was a lot of hugging and handshaking," Marcus recalls. He adds that although some of the older people were mourning townspeople they had known who were lost in the Holocaust, much younger people, even the children, seemed to "get it" too. "It was so amazing-they were really understanding the significance of this," he says. "I've never heard of another story where people in a town have gone out of their way to rebuild and maintain a synagogue, to keep the (Jewish) cemetery intact." After the services Lolek, the Lostice mayor, invited the Chicago delegation back to his office, where he proudly served a cheese made in the region and poured a strong, vodka-like drink, made from plums and also produced locally. When he found out that one congregant, Jerry Friedman, is a former mayor (Friedman was the mayor of Northbrook 24 years ago), "he insisted I have another, then he got somebody to take our picture," Friedman relates. The visit ended for the Chicagoans with a trip to a 13th-century castle just outside of the town. The Nazis had once used it for their regional headquarters, but now it held an exhibit documenting the history of the Jewish community of Lostice, put together by the director of the Respect and Tolerance Foundation. He had also engaged an Irish violin and piano duo, flying them in to play Jewish music (although the musicians are non-Jews) interspersed with Jewish poetry at the close of Shabbat. For Elder, "sitting in this room, hearing this music in the very room where Nazis used to listen to Wagner while planning to deport Jews, was such an incredible experience." Indeed, Elder says that for everyone who participated, the trip was "life- changing." Some, like Joseph, have kept up and deepened the connections they made. An artist who specializes in ketubot (wedding certificates), she met an artist from Lostice and they began working on arranging a joint exhibition together in a nearby town. In addition, the non-Jewish Czech artist began making a Jewish calendar and sought Joseph's help in writing the names of the months in Hebrew. Beyond that, "I learned something," Joseph says. "I never really appreciated the cultural loss to these European communities when their Jews were eliminated. I was raised to think the gentiles were willing participants, and in some cases they were." But in Lostice, and perhaps other towns too, "they felt a terrible loss," she says. "Now they are teaching their kids about it and using that to promote respect and tolerance." Discovering that was "unbelievable," Joseph says. "I was filled with a mixture of sorrow that the Jewish community was completely absent and just being amazed that the gentiles of the town were making this huge effort to document and educate about the Jewish heritage." The trip "was two days, but it's continued to blossom for me in terms of my connecting with people who are promoting something really good in the world," she says. Friedman says it's not just the participants, but even those who didn't go along who were impacted. "The synagogue has been very touched by the whole experience," he says. "The entire synagogue, they want to know more about it. Every time we have services people are constantly asking abut the trip, about our experiences." For Marcus, who has studied the Holocaust academically, "this was absolutely unique-a town in central Europe that has really embraced the lessons of the Holocaust and is going out of its way to understand." Shteipel, the respect and Tolerance Foundation director, "is going around the country teaching the Holocaust to children in public schools who don't even know what the Holocaust is, and they're listening. It's so rare that the lessons of the Holocaust-never forget-are actually being applied here," he says. Schakowsky, he adds, participated vicariously even though her legislative duties prevented her from taking the trip. "From the day the rabbi approached Jan she was so thrilled, she was checking in on this every day," he says. "There was such a sense of accomplishment and pride when we finally got it wrapped up." For her part, Schakowsky says she sensed that the visit "had this huge educational impact. It was so loaded with emotion, not like reading it in a textbook. I had a sense of that, the potential, when Rabbi Elder called." She says she is grateful to Elder for "engaging so many people, governments, people's hearts, the significance of how much this would mean to the people of the little community and beyond." Elder himself continues to be amazed by "the stories, the connections- incredible layers of them. You throw a rock into a river and it creates a ripple effect and you have no idea. The ripples just keep going." That's certainly true of the Lostice story. Currently Czech filmmakers are working on a documentary about the community, and the story of the Torah's return will be a part of it. In addition the Westminster Synagogue in London, which is still involved with distributing Czech Torahs all over the world, plans to use the story of the Lostice Torah as a paradigm for reconnecting the past and present of lost Jewish communities. The Respect and Tolerance Foundation is continuing to gather information about the Jews of Lostice and two surrounding towns and will eventually show their findings to the public through an exhibition and possibly a book. "History of Jewish settlement in our region goes back to the 15th century, but very little attention has been given to this subject so far," foundation director Shteipel writes in an e-mail explaining the organization's work. "The history of the Jewish communities in the Lostice area until the Nazi occupation is a story of peaceful coexistence of Jewish and Christian inhabitants. There is plenty of evidence that in the period before World War II, Jews were fully integrated into the society and took vital part in cultural and social life of their towns," he writes. The work the foundation is doing, he continues, "can be used as evidence that tolerant coexistence of people with different religious and racial backgrounds was, and is, possible. In our divided world such a message is still essential and very important." He closes with a quote from Elie Wiesel: "To remain silent and indifferent is the greatest sin of all." Robert Marcus, too, believes that the Lostice trip "can be used to reconnect other little towns with other American communities. I've never heard of one like this before," he says. "This was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity." And he speaks for everyone involved in the journey when he says, "I want people to know that even with the rise of anti-Semitism in the world, there are opportunities to rekindle the lessons of the Holocaust." |

© 1999-2006, The Czech Torah Network. All Rights Reserved.

The logo design was created by Risa Mandelberg and is being used with permission.

© 1997, the paperdoll company. All Rights Reserved.

For questions or comments about this Web site please e-mail The Czech Torah Network at czechtorah@aol.com.